Reorganize docs/arch (#12270)

@@ -46,5 +46,4 @@ The [`tests/`](tests/) subdirectory includes unit and fuctional tests that run a

|

||||

## Everything else

|

||||

|

||||

- [docker](docker/): All dbt versions are published as Docker images on DockerHub. This subfolder contains the `Dockerfile` (constant) and `requirements.txt` (one for each version).

|

||||

- [etc](etc/): Images for README

|

||||

- [scripts](scripts/): Helper scripts for testing, releasing, and producing JSON schemas. These are not included in distributions of dbt, nor are they rigorously tested—they're just handy tools for the dbt maintainers :)

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1,5 +1,5 @@

|

||||

<p align="center">

|

||||

<img src="https://raw.githubusercontent.com/dbt-labs/dbt-core/fa1ea14ddfb1d5ae319d5141844910dd53ab2834/etc/dbt-core.svg" alt="dbt logo" width="750"/>

|

||||

<img src="https://raw.githubusercontent.com/dbt-labs/dbt-core/fa1ea14ddfb1d5ae319d5141844910dd53ab2834/docs/images/dbt-core.svg" alt="dbt logo" width="750"/>

|

||||

</p>

|

||||

<p align="center">

|

||||

<a href="https://github.com/dbt-labs/dbt-core/actions/workflows/main.yml">

|

||||

@@ -9,7 +9,7 @@

|

||||

|

||||

**[dbt](https://www.getdbt.com/)** enables data analysts and engineers to transform their data using the same practices that software engineers use to build applications.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

## Understanding dbt

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -17,7 +17,7 @@ Analysts using dbt can transform their data by simply writing select statements,

|

||||

|

||||

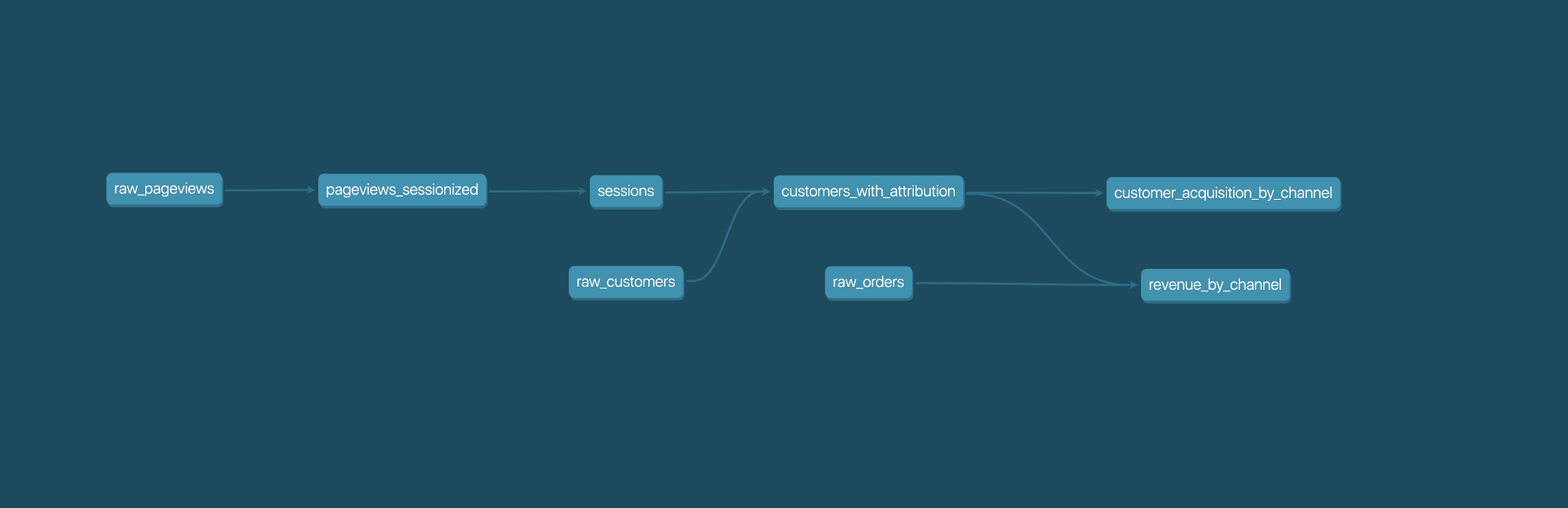

These select statements, or "models", form a dbt project. Models frequently build on top of one another – dbt makes it easy to [manage relationships](https://docs.getdbt.com/docs/ref) between models, and [visualize these relationships](https://docs.getdbt.com/docs/documentation), as well as assure the quality of your transformations through [testing](https://docs.getdbt.com/docs/testing).

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

## Getting started

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1,11 +0,0 @@

|

||||

## ADRs

|

||||

|

||||

For any architectural/engineering decisions we make, we will create an ADR (Architectural Design Record) to keep track of what decision we made and why. This allows us to refer back to decisions in the future and see if the reasons we made a choice still holds true. This also allows for others to more easily understand the code. ADRs will follow this process:

|

||||

|

||||

- They will live in the repo, under a directory `docs/arch`

|

||||

- They will be written in markdown

|

||||

- They will follow the naming convention [`adr-NNN-<decision-title>.md`](http://adr-nnn.md/)

|

||||

- `NNN` will just be a counter starting at `001` and will allow us easily keep the records in chronological order.

|

||||

- The common sections that each ADR should have are:

|

||||

- Title, Context, Decision, Status, Consequences

|

||||

- Use this article as a reference: [https://cognitect.com/blog/2011/11/15/documenting-architecture-decisions](https://cognitect.com/blog/2011/11/15/documenting-architecture-decisions)

|

||||

@@ -1,35 +0,0 @@

|

||||

# Performance Regression Framework

|

||||

|

||||

## Context

|

||||

We want the ability to benchmark our perfomance overtime with new changes going forward.

|

||||

|

||||

### Options

|

||||

- Static Window: Compare the develop branch to fastest version and ensure it doesn't exceed a static window (i.e. time parse on develop and time parse on 0.20.latest and make sure it's not more than 5% slower)

|

||||

- Pro: quick to run

|

||||

- Pro: simple to implement

|

||||

- Con: rerunning a failing test could get it to pass in a large number of changes.

|

||||

- Con: several small regressions could press us up against the threshold requiring us to do unexpected additional performance work, or lower the threshold to get a release out.

|

||||

- Variance-aware Testing: Run both the develop branch and our fastest version *many times* to collect a set of timing data. We can fail on a static window based on medians, confidence interval midpoints, and even variance magnitude.

|

||||

- Pro: would catch more small performance regressions

|

||||

- Con: would take much longer to run

|

||||

- Con: Need to be very careful about making sure caching doesn't wreck the curve (or if it does, it wrecks the curve equally for all tests)

|

||||

- Stateful Tracking: For example, the rust compiler team does some [bananas performance tracking](https://perf.rust-lang.org/). This option could be done in tandem with the above options, however it would require results be stored somewhere.

|

||||

- Pro: we can graph our performance history and look really cool.

|

||||

- Pro: Variance-aware testing would run in half the time since you can just reference old runs for comparison

|

||||

- Con: state in tests sucks

|

||||

- Con: longer to build

|

||||

- Performance Profiling: Running a sampling-based profiler through a series of standardized test runs (test designed to hit as many/all of the code paths in the codebase) to determine if any particular function/class/other code has regressed in performance.

|

||||

- Pro: easy to find the cause of the perf. regression

|

||||

- Pro: should be able to run on a fairly small project size without losing much test resolution (a 5% change in a function should be evident with even a single case that runs that code path)

|

||||

- Con: complex to build

|

||||

- Con: compute intensive

|

||||

- Con: requires stored results to compare against

|

||||

|

||||

## Decision

|

||||

We decided to start with variance-aware testing with the ability to add stateful tracking by leveraging `hyperfine` which does all the variance work for us, and outputs clear json artifacts. Since we're running perfornace testing on a schedule it doesn't matter that as we add more tests it may take hours to run. The artifacts are all stored in the github action runs today, but could easily be changed to be sent somewhere in the action to track over time.

|

||||

|

||||

## Status

|

||||

Completed

|

||||

|

||||

## Consequences

|

||||

We now have the ability to more rigorously detect performance regressions, but we do not have a solid way to identify where that regression is coming from. Adding Performance Profiling cababilities will help with this, but for now just running it nightly should help us narrow it down to specific commits. As we add more performance tests, the testing matrix may take hours to run which consumes resources on GitHub Actions. Because performance testing is asynchronous, failures are easier to miss or ignore, and because it is non-deterministic it adds a non-trivial amount of complexity to our development process.

|

||||

@@ -1,34 +0,0 @@

|

||||

# Structured Logging Arch

|

||||

|

||||

## Context

|

||||

Consumers of dbt have been relying on log parsing well before this change. However, our logs were never optimized for programatic consumption, nor were logs treated like a formal interface between dbt and users. dbt's logging strategy was changed explicitly to address these two realities.

|

||||

|

||||

### Options

|

||||

#### How to structure the data

|

||||

- Using a library like structlog to represent log data with structural types like dictionaries. This would allow us to easily add data to a log event's context at each call site and have structlog do all the string formatting and io work.

|

||||

- Creating our own nominal type layer that describes each event in source. This allows event fields to be enforced statically via mypy accross all call sites.

|

||||

|

||||

#### How to output the data

|

||||

- Using structlog to output log lines regardless of if we used it to represent the data. The defaults for structlog are good, and it handles json vs text and formatting for us.

|

||||

- Using the std lib logger to log our messages more manually. Easy to use, but does far less for us.

|

||||

|

||||

## Decision

|

||||

#### How to structure the data

|

||||

We decided to go with a custom nominal type layer even though this was going to be more work. This type layer centralizes our assumptions about what data each log event contains, and allows us to use mypy to enforce these centralized assumptions acrosss the codebase. This is all for the purpose for treating logs like a formal interface between dbt and users. Here are two concrete, practical examples of how this pattern is used:

|

||||

|

||||

1. On the abstract superclass of all events, there are abstract methods and fields that each concrete class must implement such as `level_tag()` and `code`. If you make a new concrete event type without those, mypy will fail and tell you that you need them, preventing lost log lines, and json log events without a computer-friendly code.

|

||||

|

||||

2. On each concrete event, the fields we need to construct the message are explicitly in the source of the class. At every call site if you construct an event without all the necessary data, mypy will fail and tell you which fields you are missing.

|

||||

|

||||

Using mypy to enforce these assumptions is a step better than testing becacuse we do not need to write tests to run through every branch of dbt that it could take. Because it is checked statically on every file, mypy will give us these guarantees as long as it is configured to run everywhere.

|

||||

|

||||

#### How to output the data

|

||||

We decided to use the std lib logger because it was far more difficult than we expected to get to structlog to work properly. Documentation was lacking, and reading the source code wasn't a quick way to learn. The std lib logger was used mostly out of a necessity, and because many of the pleasantries you get from using a log library we had already chosen to do explicitly with functions in our nominal typing layer. Swapping out the std lib logger in the future should be an easy task should we choose to do it.

|

||||

|

||||

## Status

|

||||

Completed

|

||||

|

||||

## Consequences

|

||||

Adding a new log event is more cumbersome than it was previously: instead of writing the message at the log callsite, you must create a new concrete class in the event types. This is more opaque for new contributors. The json serialization approach we are using via `asdict` is fragile and unoptimized and should be replaced.

|

||||

|

||||

All user-facing log messages now live in one file which makes the job of conforming them much simpler. Because they are all nominally typed separately, it opens up the possibility to have log documentation generated from the type hints as well as outputting our logs in multiple human languages if we want to translate our messages.

|

||||

@@ -1,68 +0,0 @@

|

||||

# Python Model Arch

|

||||

|

||||

## Context

|

||||

We are thinking of supporting `python` ([roadmap](https://github.com/dbt-labs/dbt-core/blob/main/docs/roadmap/2022-05-dbt-a-core-story.md#scene-3-python-language-dbt-models), [discussion](https://github.com/dbt-labs/dbt-core/discussions/5261)) as a language other than SQL in dbt-core. This would allow users to express transformation logic that is tricky to do in SQL and have more libraries available to them.

|

||||

|

||||

### Options

|

||||

|

||||

#### Where to run the code

|

||||

- running it locally where we run dbt core.

|

||||

- running it in the cloud providers' environment.

|

||||

|

||||

#### What are the guardrails dbt would enforce for the python model

|

||||

- None, users can write whatever code they like.

|

||||

- focusing on data transformation logic where each python model should have a model function that returns a database object for dbt to materialize.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Where should the implementation live

|

||||

Two places we need to consider are `dbt-core` and each individual adapter code-base. What are the pieces needed? How do we decide what goes where?

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

#### Are we going to allow writing macros in python

|

||||

- Not allowing it.

|

||||

- Allowing certain Jinja templating

|

||||

- Allow everything

|

||||

|

||||

## Decisions

|

||||

#### Where to run the code

|

||||

In the same idea of dbt is not your query engine, we don't want dbt to be your python runtime. Instead, we want dbt to focus on being the place to express transformation logic. So python model will be following the existing pattern of the SQL model(parse and compile user written logic and submit it to your computation engine).

|

||||

|

||||

#### What are the guardrails dbt would enforce for the python model

|

||||

We want dbt to focus on transformation logic, so we opt for setting up some tools and guardrails for the python model to focus on doing data transformation.

|

||||

1. A `dbt` object would have functions including `dbt.ref`, `dbt.source` function to reference other models and sources in the dbt project, the return of the function will be a dataframe of referenced resources.

|

||||

1. Code in the python model node should include a model function that takes a `dbt` object as an argument, do the data transformation logic inside, and return a dataframe in the end. We think folks should load their data into dataframes using the `dbt.ref`, `dbt.source` provided over raw data references. We also think logic to write dataframe to database objects should live in materialization logic instead of transformation code.

|

||||

1. That `dbt` object should also have an attribute called `dbt.config` to allow users to define configurations of the current python model like materialization logic, a specific version of python libraries, etc. This `dbt.config` object should also provide a clear access function for variables defined in project YAML. This way user can access arbitrary configuration at runtime.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Where should the implementation live

|

||||

|

||||

Logic in core should be universal and carry the opionions we have for the feature, this includes but not limited to

|

||||

1. parsing of python file in dbt-core to get the `ref`, `source`, and `config` information. This information is used to place the python model in the correct place in project DAG and generate the correct python code sent to compute engine.

|

||||

1. `language` as a new top-level node property.

|

||||

1. python template code that is not cloud provider-specific, this includes implementation for `dbt.ref`, `dbt.source`. We would use ast parser to parse out all of the `dbt.ref`, `dbt.source` inside python during parsing time, and generate what database resources those points to during compilation time. This should allow user to copy-paste the "compiled" code, and run it themselves against the data warehouse — just like with SQL models. A example of definition for `dbt.ref` could look like this

|

||||

```python

|

||||

def ref(*args):

|

||||

refs = {"my_sql_model": "DBT_TEST.DBT_SOMESCHEMA.my_sql_model"}

|

||||

key = ".".join(args)

|

||||

return load_df_function(refs[key])

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

1. functional tests for the python model, these tests are expected to be inherited in the adapter code to make sure intended functions are met.

|

||||

1. Generalizing the names of properties (`sql`, `raw_sql`, `compiled_sql`) for a future where it's not all SQL.

|

||||

1. implementation of restrictions have for python model.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Computing engine specific logic should live in adapters, including but not limited to

|

||||

- `load_df_function` of how to load a dataframe for a given database resource,

|

||||

- `materialize` of how to save a dataframe to table or other materialization formats.

|

||||

- some kind of `submit_python` function for submitting python code to compute engine.

|

||||

- addition or modification `materialization` macro to add materialize the python model

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

#### Are we going to allow writing macros in python

|

||||

|

||||

We don't know yet. We use macros in SQL models because it allows us to achieve what SQL can't do. But with python being a programming language, we don't see a strong need for macros in python yet. So we plan to strictly disable that in the user-written code in the beginning, and potentially add more as we hear from the community.

|

||||

|

||||

## Status

|

||||

Implementing

|

||||

|

||||

# Consequences

|

||||

Users would be able to write python transformation models in dbt and run them as part of their data transformation workflow.

|

||||

@@ -1,53 +0,0 @@

|

||||

# Use of betterproto package for generating Python message classes

|

||||

|

||||

## Context

|

||||

We are providing proto definitions for our structured logging messages, and as part of that we need to also have Python classes for use in our Python codebase

|

||||

|

||||

### Options, August 30, 2022

|

||||

|

||||

#### Google protobuf package

|

||||

|

||||

You can use the google protobuf package to generate Python "classes", using the protobuf compiler, "protoc" with the "--python_out" option.

|

||||

|

||||

* It's not readable. There are no identifiable classes in the output.

|

||||

* A "class" is generated using a metaclass when it is used.

|

||||

* You can't subclass the generated classes, which don't act much like Python objects

|

||||

* Since you can't put defaults or methods of any kind in these classes, and you can't subclass them, they aren't very usable in Python.

|

||||

* Generated classes are not easily importable

|

||||

* Serialization is via external utilities.

|

||||

* Mypy and flake8 totally fail so you have to exclude the generated files in the pre-commit config.

|

||||

|

||||

#### betterproto package

|

||||

|

||||

* It generates readable "dataclass" classes.

|

||||

* You can subclass the generated classes. (Though you still can't add additional attributes. But if we really needed to we might be able to modify the source code to do so.)

|

||||

* Integrates much more easily with our codebase.

|

||||

* Serialization (to_dict and to_json) is built in.

|

||||

* Mypy and flake8 work on generated files.

|

||||

|

||||

* Additional benefits listed: [betterproto](https://github.com/danielgtaylor/python-betterproto)

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

## Revisited, March 21, 2023

|

||||

|

||||

We are switching away from using betterproto because of the following reasons:

|

||||

* betterproto only suppports Optional fields in a beta release

|

||||

* betterproto has had only beta releases for a few years

|

||||

* betterproto doesn't support Struct, which we really need

|

||||

* betterproto started changing our message names to be more "pythonic"

|

||||

|

||||

Steps taken to mitigate the drawbacks of Google protobuf from above:

|

||||

* We are using a wrapping class around the logging events to enable a constructor that looks more like a Python constructor, as long as only keyword arguments are used.

|

||||

* The generated file is skipped in the pre-commit config

|

||||

* We can live with the awkward interfaces. It's just code.

|

||||

|

||||

Advantages of Google protobuf:

|

||||

* Message can be constructed from a dictionary of all message values. With betterproto you had to pre-construct nested message objects, which kind of forced you to sprinkle generated message objects through the codebase.

|

||||

* The Struct support works really well

|

||||

* Type errors are caught much earlier and more consistently. Betterproto would accept fields of the wrong types, which was sometimes caught on serialization to a dictionary, and sometimes not until serialized to a binary string. Sometimes not at all.

|

||||

|

||||

Disadvantages of Google protobuf:

|

||||

* You can't just set nested message objects, you have to use CopyFrom. Just code, again.

|

||||

* If you try to stringify parts of the message (like in the constructed event message) it outputs in a bizarre "user friendly" format. Really bad for Struct, in particular.

|

||||

* Python messages aren't really Python. You can't expect them to *act* like normal Python objects. So they are best kept isolated to the logging code only.

|

||||

* As part of the not-really-Python, you can't use added classes to act like flags (Cache, NoFile, etc), since you can only use the bare generated message to construct other messages.

|

||||

|

Before Width: | Height: | Size: 97 KiB After Width: | Height: | Size: 97 KiB |

|

Before Width: | Height: | Size: 7.1 KiB After Width: | Height: | Size: 7.1 KiB |

|

Before Width: | Height: | Size: 138 KiB After Width: | Height: | Size: 138 KiB |

|

Before Width: | Height: | Size: 49 KiB After Width: | Height: | Size: 49 KiB |